Art from nothing, beauty from waste, discarded pieces collected, polished, refitted, and reassembled to be brought to flight again. Restorations are never exactly as they were but better, more beautiful, and stronger than before. Watching Buddy’s parts be put together for seven years at Kimball’s, to most people they looked like a pile of junk in a shed. An old frame, a rusted motor mount, chemical eaten duster wings, boxes and boxes of metal bits and pieces that would eventually come together to form my beautiful Speedmail. I made monthly trips to visit my parts for years. I would stand in the storage shed and look at them, not sure how Kimball’s were going to do it, but I could see clearly what he was going to be. With all the wondrous metal machining and engineering they put into building Buddy, the most transformational part of the restoration for me, was when they started the fabric work. When my plane was covered, stitched in fabric and painted, he came to life, and taught me a very important life lesson.

When I returned to Lake Geneva this winter after barnstorming, I looked around to see what was missing. I needed to shift my focus and discover a source, a different building block to start my Invisible Empire. I call it “invisible” because no one else sees it but me. My Invisible Empire is shaped like a Richardson Romanesque arch, arcing over my head. Constructed of conceptual wedge shaped “idea stones” or voussoir’s, representing projects I have in progress, even if only in my mind. It’s a big arch, supporting a Jimmie Allen Flying Club comic, a festival of UP to cultivate curiosity, creativity, and rethink what flying means to everyone, a foundation to get at-risk teens life coaching in my airplane, a children’s book, promotional air tours, and many more aspirations. In order to be the architect of such a massive structure, I needed to find the first idea stone, the right virtual voussoir to lay in place to start building upon. Then see if my Invisible Empire arch holds, or it crumbles to the ground, and if so try another one. I am a bit of a pattern watcher and sometimes I like to work backwards. I begin by noticing the absence of something, before I notice the presence of something else. In November I started noticing the absence of trash around me. Lake Geneva is very clean for a city with a lot of tourism. In the alley behind my apartment there are as many recycling bins, as their are trash containers. So I started watching trash. What filled up bags the most? What filled up the bins the most? Cardboard, hmmmm, interesting. I started thinking about cardboard. Where it came from, where it went to, and what I could make out of it? I discovered that paper was Wisconsin’s number one resource, and that it could be 100% recycled. How can I make cardboard inspire everyone to fly, and who are the people who need to believe they can fly the most? I looked at cardboard for a while, until I saw what was missing.

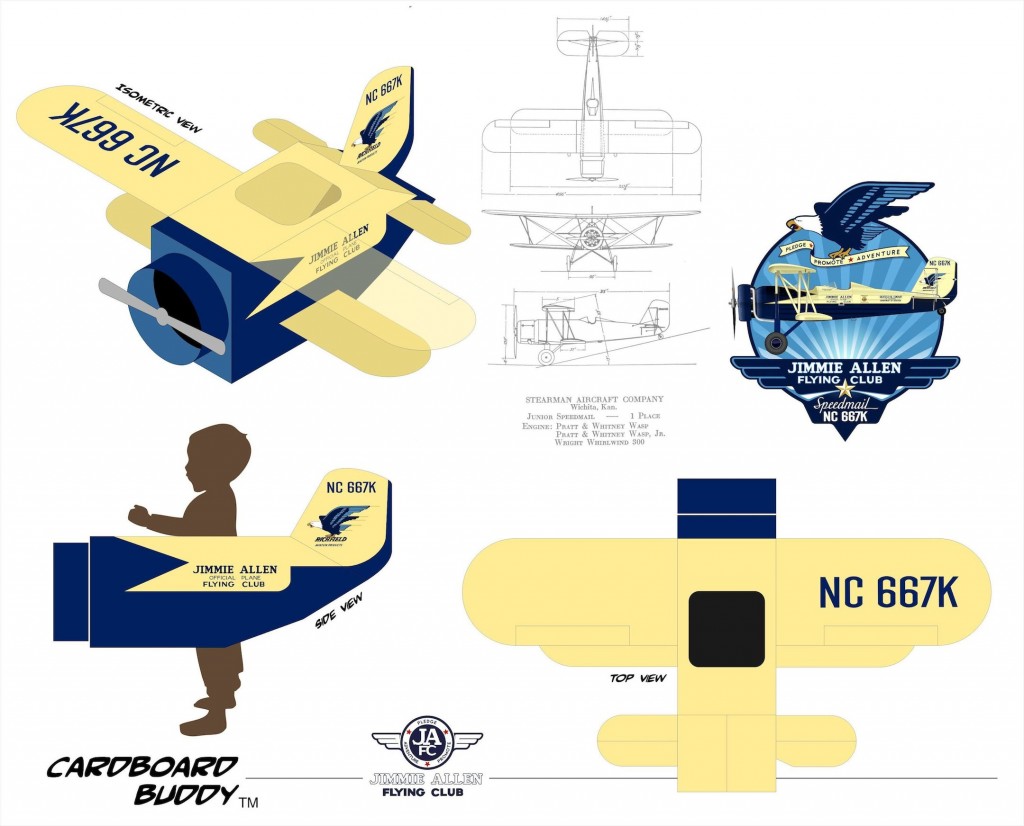

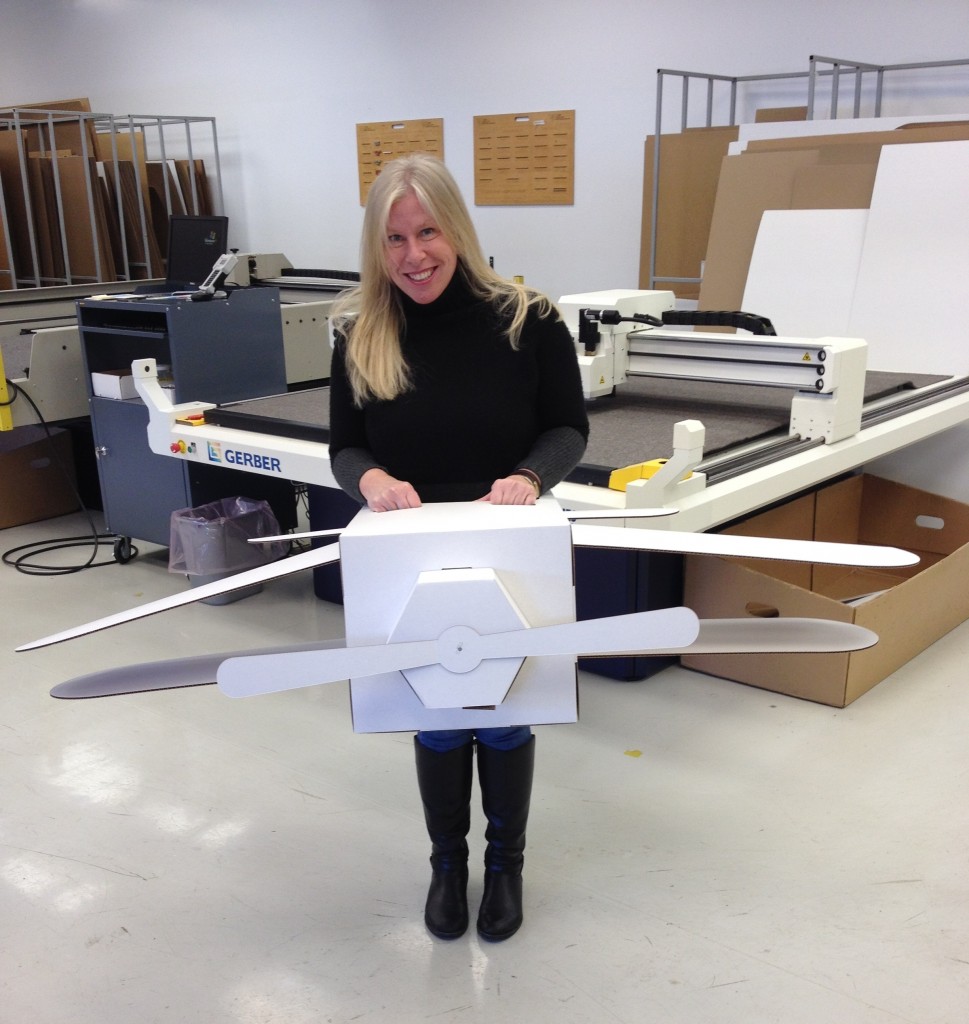

Late one night I  emailed my friend Mirco in Italy to ask a question, “Wasn’t the best present you ever got, the giant cardboard box it came in?” I attached a picture of a little boy in a cardboard airplane and my idea for designing a “Cardboard Buddy.” He shot back a picture of a race car he and his wife Monica built out of an appliance box for their son. Seems we were going to make toys. We started to design a buildable, wearable, customizable, “Cardboard Buddy.” I sent the concept to my friend Ben Redman and he helped out with measurements of his little boy, so we could scale it. Then I found a local manufacturer to build them right up the road at Wisconsin Packaging, who would outsource the assembly and packaging to another local company, who employ’s handicapped workers. Even though we’re still finishing the concept design, strengthening the wings and adding N-struts, this “idea stone” seems to be holding up pretty well. When the design is finished we are going use the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, to raise enough money to build a limited edition. So we can give the template away for free on my website, and donate the majority of “Cardboard Buddy’s” to children’s organizations and shelters.

emailed my friend Mirco in Italy to ask a question, “Wasn’t the best present you ever got, the giant cardboard box it came in?” I attached a picture of a little boy in a cardboard airplane and my idea for designing a “Cardboard Buddy.” He shot back a picture of a race car he and his wife Monica built out of an appliance box for their son. Seems we were going to make toys. We started to design a buildable, wearable, customizable, “Cardboard Buddy.” I sent the concept to my friend Ben Redman and he helped out with measurements of his little boy, so we could scale it. Then I found a local manufacturer to build them right up the road at Wisconsin Packaging, who would outsource the assembly and packaging to another local company, who employ’s handicapped workers. Even though we’re still finishing the concept design, strengthening the wings and adding N-struts, this “idea stone” seems to be holding up pretty well. When the design is finished we are going use the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, to raise enough money to build a limited edition. So we can give the template away for free on my website, and donate the majority of “Cardboard Buddy’s” to children’s organizations and shelters.

There is a beautiful strength in the gentle nature of fabric airplanes and even cardboard ones, that mimics our lives and connects us to them in remarkable ways. Many aircraft owners have a symbiotic relationship with their planes. I seem to be inexplicably tied to mine always. A friend once said to me that our planes are our children, but I see my planes as my mentors. Wiser than me, teaching me lessons, as I try to keep up with the homework they give. What my Speedmail taught me during his restoration was that I was in need of a restoration myself. I had too many pieces of metal built up on my exterior and not enough fabric, and that was compromising my structural integrity.

There is a beautiful strength in the gentle nature of fabric airplanes and even cardboard ones, that mimics our lives and connects us to them in remarkable ways. Many aircraft owners have a symbiotic relationship with their planes. I seem to be inexplicably tied to mine always. A friend once said to me that our planes are our children, but I see my planes as my mentors. Wiser than me, teaching me lessons, as I try to keep up with the homework they give. What my Speedmail taught me during his restoration was that I was in need of a restoration myself. I had too many pieces of metal built up on my exterior and not enough fabric, and that was compromising my structural integrity.

I’ve spent most of my life in the company of men. Tagging along with the boys since childhood, and traveling the country on boats and planes with them. I love their company. I guess I prefer the directness of a verbal punch over a passive aggressive pinch any day, but men can be pretty tough. Flying alongside the boys for twenty years, I had been trying to be as tough as them. It wasn’t until a series of stresses, a number of sadnesses came along in sequence. One after another during the final years of Buddy’s restoration, that my tough exterior started to crack from mental metal fatigue, and all that toughness started to fall away. Which is a good thing, but when I got one really hard life punch, I didn’t have the exterior metal I was accustomed to wearing to protect me and that blow caused some serious structural failure. When I was there, in despair, leaking from every pore in my body, without any armor left, my plane reminded me I only had two choices. To put all that metal back on, reapply all those tough exterior parts I had used as a brace, or leave them off and lighten up. I listened to him and started enlightening myself with the strength of knowledge, and empowering myself with the power of love and kindness. I learned the only armor I would ever need would be found in the friendship of people who were looking to lighten up, and enlighten themselves as well. Change is hard for people, it makes them uncomfortable, and when you change inevitably the skeptics question, “Who does she think she is?” I won’t answer them except to say. I am not exactly who I was, or yet exactly who I will be. I am a project in progress.