7,277 nautical miles flown. 1,466 gallons of fuel burned. 4,187 minutes in the air. 149 days with my plane. Why? Why do I do this, not just once, but summer after summer. What am I looking for?

7,277 nautical miles flown. 1,466 gallons of fuel burned. 4,187 minutes in the air. 149 days with my plane. Why? Why do I do this, not just once, but summer after summer. What am I looking for?

Pilot’s say to me, “you’re living the dream,” but what is that? The dream, and where is that giant dream for them, in little me, flying my little biplane across a giant landscape? I don’t think of flying as living the dream, I just think of it as part of what I do, to be authentically who I am. I fly because it’s the most difficult and most natural thing I’ve ever done in my life. It’s the only thing I’ve ever began without coercion or influence. I found my way to it completely on my own, unaware that a discovery flight twenty years ago, would force me to discover myself. Flying open-cockpit biplanes long distance’s across the country is one of the most joyful parts of my life, it is also painfully ephemeral, short-lived. But while it lasts, I choose to wear my heart on my wing, outside my body barnstorming in the summer, and break it open again each fall when I return to tuck my plane back in his hangar. My heart remains separated from me, beating as if it were attached to Lindbergh’s profusion pump. Glassed in, in the warm walls of Florida. Until the snow melts and the fields turn green, signaling our spring escape into the sentimental cartography of our path home.

Is the dream pilots speak of to me an escape from captivity, or is it deeper than that? I listened to you, with hearts breaking in front of me, every day on tour this year. Choking on your frustration and fear that you’re about to lose something you love. I spend a lot of time listening to people. In my front seat, my friend St Exupery who flies with me everywhere, shared your heart break – watching his tribe decimated, torn apart in World War II. He was in exile, and not such a beautiful one as mine. Separated from his planes that were held captive in France by Nazi Germany. St. Ex even built coffin-like submarine models, and underwater fish-shaped transports in his bathtub in New York City. Dreaming of how to sneak his planes out of his homeland, under the water. He only wanted to put his heart back into his body, to fly below the clouds over France again…to feel whole. Charles Lindbergh, who occupies my cockpit quite literally, having flown Buddy in 1930, had his heart broken again and again. Between the years of 1930-1934, Lindbergh worked on a perfusion pump, in collaboration with Dr. Carrel at the Rockefeller Institute, on an experiment to keep detached organs alive. In September, 1935, Carrel and Lindbergh co-published, An Apparatus for the Culture of Whole Organs, just a few months before the Lindbergh’s went into exile in England. Escaping the greatest heart break, the murder of their child, and the press that hounded them mercilessly during “the trial of the century.” Lindbergh’s pump wasn’t an artificial heart, it was a way of keeping a whole heart alive outside the body, in an artificial environment.

I spent this long summer having pilots share their dreams and their nightmares with me. Shyly admitting to me that you read my blog like a guilty secret. Showing me your whole heart, the only way you know how, through our common language of flying. Somedays your fear was exhausting and it overwhelmed me. You cried and yelled, time and again, trying to express what you were trying to hold on to, holding your heart in your hands. So afraid that the dream of flying was dying that you couldn’t see that it was right in front of you, beating outside your body, alive. I wish you could see what I see, that the dream is there for everyone, and it’s different for everyone. People are flying on motorcycles, they’re flying in boats, and with model airplanes. Flying down country roads on horses, flying in their cars with music blaring, flying in their parents arms, on dance floors, and surfboards. Millions of people are flying each day with their hands arched like airfoils out the windows of vehicles all across the world. To understand what I see in the air, what I’m looking for, is to accept that the dream isn’t about airplanes, it’s about people. That the dream of flying, belongs to everyone.

I spent this long summer having pilots share their dreams and their nightmares with me. Shyly admitting to me that you read my blog like a guilty secret. Showing me your whole heart, the only way you know how, through our common language of flying. Somedays your fear was exhausting and it overwhelmed me. You cried and yelled, time and again, trying to express what you were trying to hold on to, holding your heart in your hands. So afraid that the dream of flying was dying that you couldn’t see that it was right in front of you, beating outside your body, alive. I wish you could see what I see, that the dream is there for everyone, and it’s different for everyone. People are flying on motorcycles, they’re flying in boats, and with model airplanes. Flying down country roads on horses, flying in their cars with music blaring, flying in their parents arms, on dance floors, and surfboards. Millions of people are flying each day with their hands arched like airfoils out the windows of vehicles all across the world. To understand what I see in the air, what I’m looking for, is to accept that the dream isn’t about airplanes, it’s about people. That the dream of flying, belongs to everyone.

I know my tribe of pilots feels responsible to be the gatekeepers, the guardians of the dream of flying. I’m sorry to tell you, but we’ve made quite a mess of it, the pilots. The key is my friends, and maybe the key around my neck is, the dream is not ours. I know it’s so tempting to lock it up, and hold it captive in your hangars, and protect it because it’s so beautiful and judge others for not being good enough. But the only way that it can survive is to share it, talk about it, and keep it alive, in its natural environment, in our hearts. We can’t guard the dream, but we can be the Gardeners of it.

I know my tribe of pilots feels responsible to be the gatekeepers, the guardians of the dream of flying. I’m sorry to tell you, but we’ve made quite a mess of it, the pilots. The key is my friends, and maybe the key around my neck is, the dream is not ours. I know it’s so tempting to lock it up, and hold it captive in your hangars, and protect it because it’s so beautiful and judge others for not being good enough. But the only way that it can survive is to share it, talk about it, and keep it alive, in its natural environment, in our hearts. We can’t guard the dream, but we can be the Gardeners of it.

Fog smells hard, like river rocks you pick up and breathe in their mineral scent before they dry. Fog tastes like gray sugar-free flourless sponge cake, flavorless. Fog feels like leaches, slippery cold wet, sucking painlessly on your skin, making you uncomfortable. Fog looks like titanium white with a hair of cerulean blue, blended with a dirty sable brush dipped in week’s old turpentine. Fog moves like fear, sluggish and guarded, cowering in the hallows. Fog sounds like holding your breath underwater too long. Fog’s hunch, it’s intuition, is shame.

Fog smells hard, like river rocks you pick up and breathe in their mineral scent before they dry. Fog tastes like gray sugar-free flourless sponge cake, flavorless. Fog feels like leaches, slippery cold wet, sucking painlessly on your skin, making you uncomfortable. Fog looks like titanium white with a hair of cerulean blue, blended with a dirty sable brush dipped in week’s old turpentine. Fog moves like fear, sluggish and guarded, cowering in the hallows. Fog sounds like holding your breath underwater too long. Fog’s hunch, it’s intuition, is shame. A line of young courage shufflers had formed in front of me and Buddy, patiently waiting their turn to introduce themselves and be able to sit in my cockpit. Bright boy minds, and faces covered in pimples and curiosity, hovered around me. Their attention floating in and out of the mist that rarely leaves a teen’s existence, a home-brewed mind murk of self-consciousness. I love talking with teenagers, they’re smart, quirky, impetuous, raw and unpolished, just like me. I was having fun, laughing with a boy who was battling some serious ADD, even worse than mine. He was struggling to focus on what he was trying to tell me, when a breeze blew through the fog. Bella, Isabella flew up to me shyly singing, she was ephemeral. Isabella said without self doubt or hesitation, that she was designing a hydro-electric triplane, and that her airplane would be fueled by water. Isabella asked me, “Where do you think the ailerons would be, on which wing? My heart paused, this little mockingbird was special.

A line of young courage shufflers had formed in front of me and Buddy, patiently waiting their turn to introduce themselves and be able to sit in my cockpit. Bright boy minds, and faces covered in pimples and curiosity, hovered around me. Their attention floating in and out of the mist that rarely leaves a teen’s existence, a home-brewed mind murk of self-consciousness. I love talking with teenagers, they’re smart, quirky, impetuous, raw and unpolished, just like me. I was having fun, laughing with a boy who was battling some serious ADD, even worse than mine. He was struggling to focus on what he was trying to tell me, when a breeze blew through the fog. Bella, Isabella flew up to me shyly singing, she was ephemeral. Isabella said without self doubt or hesitation, that she was designing a hydro-electric triplane, and that her airplane would be fueled by water. Isabella asked me, “Where do you think the ailerons would be, on which wing? My heart paused, this little mockingbird was special.

Somedays are the days I break people wide-open when I fly with them, and they actually glow. They become human glow sticks so luminescent their eyes shine, and their emotion and thoughts become transparent braille, readable on the surface of their skin. I know that they have broken wide-open when their shoulders relax and they become completely still on the flight controls, when they are wordless, when the tears come. Somedays flights are the special ones, these are the people I go out of my way to fly. When they finally find me I see it in their eyes, and I hear it in their voices, that a flight to them means much more than just a flight in a rare biplane. It’s an escape tunnel towards an air bridge, from the dark where they’ve been, into the light they’re trying to get back to. Even sitting behind them, unable to see their faces, there is much being said between us without words. I know the escape route by heart. Their escape begins the moment I move my hands away from the stick up towards my windshield, and when my feet shift down off the rudder pedals to the floorboards and I say, “you’re flying the airplane.” The door to the tunnel opens, when I give up my powerful to their mend their powerless, when I give up my trust fly to break their trust fall. I put their life back in their hands along with mine, the moment I stop holding their hand, and I let go. In that fearful moment, when they first have to make all their own decisions in my big, blind biplane, they start into flow, and just fly. They forget about me and themselves and where they’ve been, and they start down the tunnel. When I see them ahead of me, flying towards the light at the end and not looking back, that’s when I know they’ve escaped. I don’t see them again until after we land and I look into their eyes, I see that they’ve changed. Their eyes are glowing back at me, like tapetum lucidum.

Somedays are the days I break people wide-open when I fly with them, and they actually glow. They become human glow sticks so luminescent their eyes shine, and their emotion and thoughts become transparent braille, readable on the surface of their skin. I know that they have broken wide-open when their shoulders relax and they become completely still on the flight controls, when they are wordless, when the tears come. Somedays flights are the special ones, these are the people I go out of my way to fly. When they finally find me I see it in their eyes, and I hear it in their voices, that a flight to them means much more than just a flight in a rare biplane. It’s an escape tunnel towards an air bridge, from the dark where they’ve been, into the light they’re trying to get back to. Even sitting behind them, unable to see their faces, there is much being said between us without words. I know the escape route by heart. Their escape begins the moment I move my hands away from the stick up towards my windshield, and when my feet shift down off the rudder pedals to the floorboards and I say, “you’re flying the airplane.” The door to the tunnel opens, when I give up my powerful to their mend their powerless, when I give up my trust fly to break their trust fall. I put their life back in their hands along with mine, the moment I stop holding their hand, and I let go. In that fearful moment, when they first have to make all their own decisions in my big, blind biplane, they start into flow, and just fly. They forget about me and themselves and where they’ve been, and they start down the tunnel. When I see them ahead of me, flying towards the light at the end and not looking back, that’s when I know they’ve escaped. I don’t see them again until after we land and I look into their eyes, I see that they’ve changed. Their eyes are glowing back at me, like tapetum lucidum. They both were special, one I knew had had a great loss, the other, I simply felt a certain sadness from. I didn’t want to fly them because I sympathized with them, I wanted to fly with them because I empathized with them. The ability to empathize with someone, to see things from their perspective and accept it as if it were your own, is the most important gift a teacher can have. It is also the greatest gift we can give to one another. I knew that I could get them on the air bridge, reconnecting them to remembering what it was like to feel fearless and full of joy, if I could give them the perfect flight.

They both were special, one I knew had had a great loss, the other, I simply felt a certain sadness from. I didn’t want to fly them because I sympathized with them, I wanted to fly with them because I empathized with them. The ability to empathize with someone, to see things from their perspective and accept it as if it were your own, is the most important gift a teacher can have. It is also the greatest gift we can give to one another. I knew that I could get them on the air bridge, reconnecting them to remembering what it was like to feel fearless and full of joy, if I could give them the perfect flight. A few days later I did give Jamie and Lu Ann their perfect flights, and they gave me mine. On a cloudless evening with chiffon air, they both flew off the grass runway at Brodhead, WI. Jamie flew first with me, then with my barnstormer friend Upside-down Brownell, where he got the chance to do loops and rolls and hammerheads, in Josh’s beautiful Waco. Lu Ann’s turn was next, and her hands were shaking when she got into my plane. She was quivering, Lu Ann admitted to me she had a huge crush on Buddy, and was blushing. Within the first five minutes she was on the controls alone, and I watched as she made her headlong dash down the tunnel. She hit the air bridge when I couldn’t get her to stop chasing the river, doing lazy eights, and turn back to the airport. After our flight we hugged each other in silence, then she laid her head on Buddy’s cowling, and she glowed. Lu Ann wrote me later that her new nickname was Fearless Fifi, but I already knew that.

A few days later I did give Jamie and Lu Ann their perfect flights, and they gave me mine. On a cloudless evening with chiffon air, they both flew off the grass runway at Brodhead, WI. Jamie flew first with me, then with my barnstormer friend Upside-down Brownell, where he got the chance to do loops and rolls and hammerheads, in Josh’s beautiful Waco. Lu Ann’s turn was next, and her hands were shaking when she got into my plane. She was quivering, Lu Ann admitted to me she had a huge crush on Buddy, and was blushing. Within the first five minutes she was on the controls alone, and I watched as she made her headlong dash down the tunnel. She hit the air bridge when I couldn’t get her to stop chasing the river, doing lazy eights, and turn back to the airport. After our flight we hugged each other in silence, then she laid her head on Buddy’s cowling, and she glowed. Lu Ann wrote me later that her new nickname was Fearless Fifi, but I already knew that. When I first started flying in my PT Stearman Blu, I bought Richard Bach’s book Nothing by Chance and read twice. It was a dreamscape, a wish book for me, for the life I wanted to build once. I had the desire to be like those men, a Barnstormer. It’s more than a story for me because I actually know Richard, and Stu MacPherson and Richard’s son Rob. I flew with Stu and Rob on the American Barnstormers Tour. I have seen that love of adventure in their eyes, and they still carry it with them, though they no longer fly across the country. They are all larger than life, real presences in my world, not just characters on a page. In one of the stories in Nothing by Chance, Richard shows Stu how to choose their barnstorming route with the help of an ant, they called it the “Ant Method of Navigation.” They followed an ant on the sectional chart as Richard instructs Stu, “You just follow him with a pen, now. Wherever he goes, we go.” The ant traveled a route that takes him right off the chart towards the piece of pie, the sugar. It is a great metaphor of the nomadic, rudderless adventure barnstorming appears to be, if you take the term “sugar” at face value. Professional Barnstormers picked their stops carefully, and the ones that thrived were master marketer’s. Perfect orchestrators of larger than life promotions, and dare-devil antics, that would draw even the most cynical towns person to a farm field to see the show, and maybe buy a ticket to fly. In barnstorming, “sugar” is money. I’m trying to understand the essence of “sugar” for me at the end of this summer, barnstorming with FiFi. I found such sweetness flying with this loving band of misfit winged things, and I flocked happily with them when I could, but drifted off route to see people and places that I loved. My definition of “Sugar” has changed, along with me. I’m more butterfly than barnstormer this year.

When I first started flying in my PT Stearman Blu, I bought Richard Bach’s book Nothing by Chance and read twice. It was a dreamscape, a wish book for me, for the life I wanted to build once. I had the desire to be like those men, a Barnstormer. It’s more than a story for me because I actually know Richard, and Stu MacPherson and Richard’s son Rob. I flew with Stu and Rob on the American Barnstormers Tour. I have seen that love of adventure in their eyes, and they still carry it with them, though they no longer fly across the country. They are all larger than life, real presences in my world, not just characters on a page. In one of the stories in Nothing by Chance, Richard shows Stu how to choose their barnstorming route with the help of an ant, they called it the “Ant Method of Navigation.” They followed an ant on the sectional chart as Richard instructs Stu, “You just follow him with a pen, now. Wherever he goes, we go.” The ant traveled a route that takes him right off the chart towards the piece of pie, the sugar. It is a great metaphor of the nomadic, rudderless adventure barnstorming appears to be, if you take the term “sugar” at face value. Professional Barnstormers picked their stops carefully, and the ones that thrived were master marketer’s. Perfect orchestrators of larger than life promotions, and dare-devil antics, that would draw even the most cynical towns person to a farm field to see the show, and maybe buy a ticket to fly. In barnstorming, “sugar” is money. I’m trying to understand the essence of “sugar” for me at the end of this summer, barnstorming with FiFi. I found such sweetness flying with this loving band of misfit winged things, and I flocked happily with them when I could, but drifted off route to see people and places that I loved. My definition of “Sugar” has changed, along with me. I’m more butterfly than barnstormer this year. I left Steamboat Springs in a booze soaked birthday haze. As we drove down from 12,500′ on the two lane pass from Aspen on the way to Denver, I started to wring out my brain and sobered to one thought. Where do I go next? Buddy was in yet another borrowed hangar in yet another airport, and I was in yet another guest bedroom in yet another city. We were both safe and well taken care of. I had totally achieved the essence of Barnstorming, we could go anywhere in the country we wanted. I have mined flight waiver email addresses and contact info, so that within a few hours I could have a bank of happy customers lined up to take flights wherever I am. I knew I could support us. But where did “I” want to go? I wanted to go home! I wanted to go home so badly I ached. I laid my head against the car window and searched for it, but I no idea of where home was except in my plane. I had carried home with me for so many years, I had lost all concept of it on the ground. The only thing I could think of was to buy a ticket to Lakeland, FL for the weekend. Get my client mailing list I had forgotten on my computer, get some fall clothes, and get my hair done. Then somehow get all of that, and me, back north to get Buddy and just fly somewhere, anywhere.

I left Steamboat Springs in a booze soaked birthday haze. As we drove down from 12,500′ on the two lane pass from Aspen on the way to Denver, I started to wring out my brain and sobered to one thought. Where do I go next? Buddy was in yet another borrowed hangar in yet another airport, and I was in yet another guest bedroom in yet another city. We were both safe and well taken care of. I had totally achieved the essence of Barnstorming, we could go anywhere in the country we wanted. I have mined flight waiver email addresses and contact info, so that within a few hours I could have a bank of happy customers lined up to take flights wherever I am. I knew I could support us. But where did “I” want to go? I wanted to go home! I wanted to go home so badly I ached. I laid my head against the car window and searched for it, but I no idea of where home was except in my plane. I had carried home with me for so many years, I had lost all concept of it on the ground. The only thing I could think of was to buy a ticket to Lakeland, FL for the weekend. Get my client mailing list I had forgotten on my computer, get some fall clothes, and get my hair done. Then somehow get all of that, and me, back north to get Buddy and just fly somewhere, anywhere. By the second day in Lakeland I was wading through a sea of dirty laundry and months of unopened mail floating on my floor, doing absolutely nothing I should be doing, and everything I wanted to do. Actually I was having a pretty good time visiting gal pals, doing hair and nails and shopping, but I was not sleeping at all. I had slept like a baby in hotel rooms and guest bedrooms all over the country, but I couldn’t sleep more than a couple hours in my own bed. On the second night I woke up at 4:10am at the foot of my bed, stuck to my comforter after crying myself to sleep. My eyes were swollen slits, and I sat up in the dark and knew I had to leave. This wasn’t home to me. I walked out to the kitchen and got a glass of water and looked at my phone, it was full of messages from friends in southern Wisconsin. For me these texts and voicemails became a map in the dark, and I started to think of where the most light was concentrated…and I saw it. I saw my route home. I have always chosen to call a place home, to live somewhere because of a job, or my husband, or family and friends. This time I knew I would find home where the most love was. That was my “sugar.”

By the second day in Lakeland I was wading through a sea of dirty laundry and months of unopened mail floating on my floor, doing absolutely nothing I should be doing, and everything I wanted to do. Actually I was having a pretty good time visiting gal pals, doing hair and nails and shopping, but I was not sleeping at all. I had slept like a baby in hotel rooms and guest bedrooms all over the country, but I couldn’t sleep more than a couple hours in my own bed. On the second night I woke up at 4:10am at the foot of my bed, stuck to my comforter after crying myself to sleep. My eyes were swollen slits, and I sat up in the dark and knew I had to leave. This wasn’t home to me. I walked out to the kitchen and got a glass of water and looked at my phone, it was full of messages from friends in southern Wisconsin. For me these texts and voicemails became a map in the dark, and I started to think of where the most light was concentrated…and I saw it. I saw my route home. I have always chosen to call a place home, to live somewhere because of a job, or my husband, or family and friends. This time I knew I would find home where the most love was. That was my “sugar.”

I will be fifty years old next Saturday, and we are flocking west on the B-29 tour. Further west than I have ever flown, to Denver, Colorado, landing at Rocky Mountain Metro two days before my birthday. Denver is home to me, because it is the home of my oldest and dearest friend, Andy. Andy has been my constant companion for thirty-five years. His mother and my mother were childhood friends, so he and I grew up just down the road from each other, in polar opposite households. Though our houses where completely different, we are exactly alike. So much so, we finish each other’s thoughts, and talk over one another in a silly, secret shared language of coded words and show tunes. I always wanted to trade my small, safe, watchful family for his big, wild, unsupervised one. I suppose Andy wanted to trade his for mine as well. When I would complain about my parents constant monitoring of my whereabouts, he would remind me how lucky I was to have someone actually care where I was. It’s taken me thirty-five years to realize he was right, now I’m proud of being loved by so many people, and being expected to check in. It is a privilege, not an imposition, and this summer I’ve all but lost my longing to disappear

I will be fifty years old next Saturday, and we are flocking west on the B-29 tour. Further west than I have ever flown, to Denver, Colorado, landing at Rocky Mountain Metro two days before my birthday. Denver is home to me, because it is the home of my oldest and dearest friend, Andy. Andy has been my constant companion for thirty-five years. His mother and my mother were childhood friends, so he and I grew up just down the road from each other, in polar opposite households. Though our houses where completely different, we are exactly alike. So much so, we finish each other’s thoughts, and talk over one another in a silly, secret shared language of coded words and show tunes. I always wanted to trade my small, safe, watchful family for his big, wild, unsupervised one. I suppose Andy wanted to trade his for mine as well. When I would complain about my parents constant monitoring of my whereabouts, he would remind me how lucky I was to have someone actually care where I was. It’s taken me thirty-five years to realize he was right, now I’m proud of being loved by so many people, and being expected to check in. It is a privilege, not an imposition, and this summer I’ve all but lost my longing to disappear

Stay away.

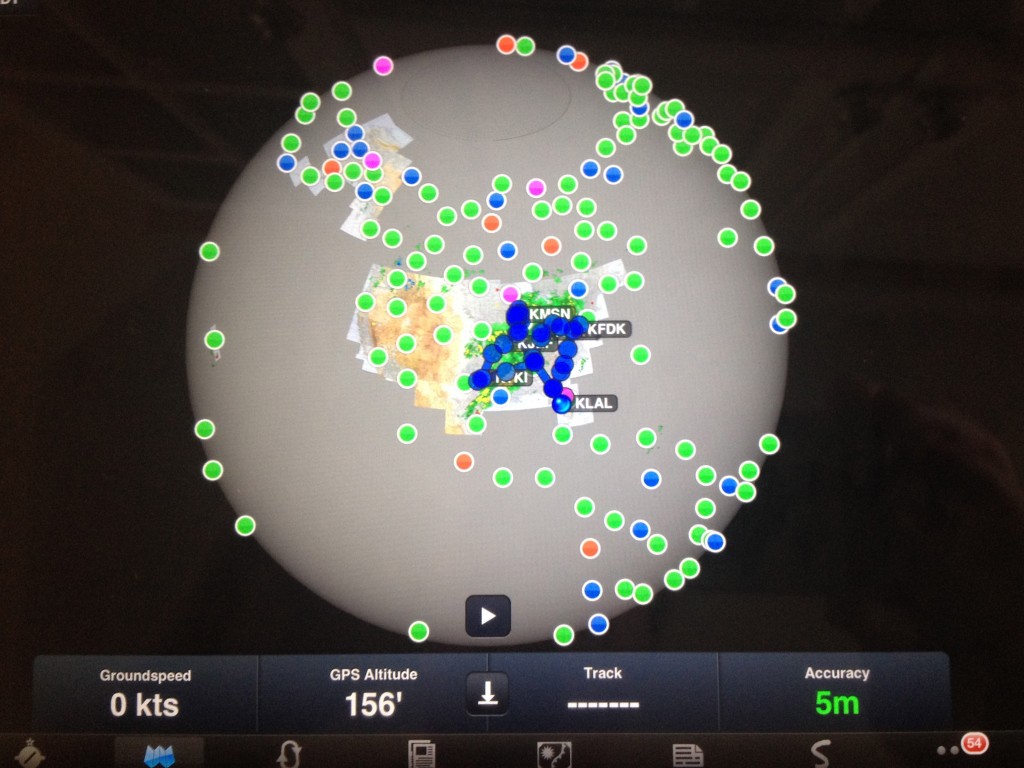

Stay away. I flew up from Brodhead to KMSN early to do some work and wait for FiFi and gang to join me for the big Bomber Show this weekend. I also have a fuel leak in my fuel selector valve and feel the responsibility to be very careful getting us into Oshkosh. The selector valve is working perfectly in the main tank position, and so there it will stay until we go to Sammy Taber’s place after Airventure. I have an ever growing army of helpers coordinating a caravan of Jimmie Allen Flying Club stuff for me north. They have gone to Herculean efforts to get everything there, and I wouldn’t miss it for the world. My best gal pal Jenny Jenn, is running all over Polk County to pick up signs and posters to deliver to Jack and Sally to be driven to Oshkosh. Wade is flying into Madison for a extra set of pilot eye’s in my front seat. The Kimball’s are driving in to Madison early to join me, and Mirco is coming in from Italy to unveil our latest creation. We are writing a graphic novel for a new Jimmie Allen Flying Club. I first met Mirco two years ago at Oshkosh, sitting with the Kimball’s in the IAC pavilion. Once Mirco and I started laughing together we never stopped. On that first meeting he said, “Sarah, you are Indiana Jones. I call you Indy from now on, because we are going together on a great adventure!” He was right, and for two years now we’ve worked on my dream of reinventing the Jimmie Allen Flying Club in a relevant way, and that it would be designed for teenagers, they are the decision-makers I really want to reach. So my Italian twin Mirco, and I have developed this wacky virtual office playground, where we Skype or FaceTime for hours to communicate across continents, while I’m flying all over the country in Buddy. I’m spending so much virtual time with him, I am now virtually part of his family. Mirco even takes me into his house on weekends, so I can say Ciao Bella to his wife Monica and his children Simone and Frederica.

I flew up from Brodhead to KMSN early to do some work and wait for FiFi and gang to join me for the big Bomber Show this weekend. I also have a fuel leak in my fuel selector valve and feel the responsibility to be very careful getting us into Oshkosh. The selector valve is working perfectly in the main tank position, and so there it will stay until we go to Sammy Taber’s place after Airventure. I have an ever growing army of helpers coordinating a caravan of Jimmie Allen Flying Club stuff for me north. They have gone to Herculean efforts to get everything there, and I wouldn’t miss it for the world. My best gal pal Jenny Jenn, is running all over Polk County to pick up signs and posters to deliver to Jack and Sally to be driven to Oshkosh. Wade is flying into Madison for a extra set of pilot eye’s in my front seat. The Kimball’s are driving in to Madison early to join me, and Mirco is coming in from Italy to unveil our latest creation. We are writing a graphic novel for a new Jimmie Allen Flying Club. I first met Mirco two years ago at Oshkosh, sitting with the Kimball’s in the IAC pavilion. Once Mirco and I started laughing together we never stopped. On that first meeting he said, “Sarah, you are Indiana Jones. I call you Indy from now on, because we are going together on a great adventure!” He was right, and for two years now we’ve worked on my dream of reinventing the Jimmie Allen Flying Club in a relevant way, and that it would be designed for teenagers, they are the decision-makers I really want to reach. So my Italian twin Mirco, and I have developed this wacky virtual office playground, where we Skype or FaceTime for hours to communicate across continents, while I’m flying all over the country in Buddy. I’m spending so much virtual time with him, I am now virtually part of his family. Mirco even takes me into his house on weekends, so I can say Ciao Bella to his wife Monica and his children Simone and Frederica.